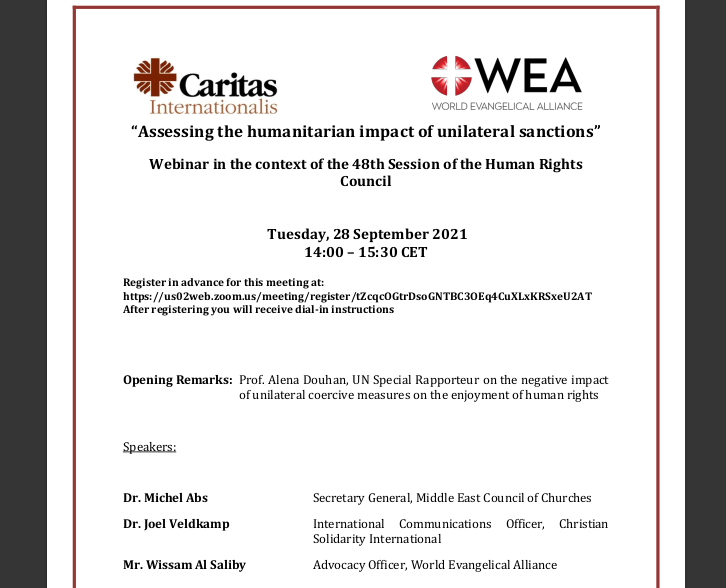

On 28 September 2021, Caritas Internationalis and the World Evangelical Alliance organized a virtual side-event, on the occasion of the 48th session of the Human Rights Council, on the topic of “Assessing the humanitarian impact of unilateral sanctions.”

The event panel consisted of prof. Alena Douhan, UN Special Rapporteur on the negative impact of unilateral coercive measures on the enjoyment of human rights, Dr. Michel Abs, Secretary General, Middle East Council of Churches, Dr. Joel Veldkamp, International Communications Officer, Christian Solidarity International, and Wissam Al Saliby, Advocacy Officer, World Evangelical Alliance. The event was moderated by Mr. Karam Abi Yazbeck, Regional coordinator, Caritas MONA.

The following is WEA’s statement at the event, delivered by Wissam al-Saliby.

The World Evangelical Alliance is a body representing 140 national evangelical alliances all over the world.

Our member and partners build partnerships across nations and borders. Churches and Evangelical organizations support each other, pursue what God has called them to do.

When there is conflict, economic crisis, mass displacement, disasters, etc. Evangelicals are among the first to move to action, serve the poor, feed the hungry, help the displaced, the refugees, and the marginalized.

The World Evangelical Alliance received reports from our members that their work, and global partnerships, are made difficult or impossible in some countries because of sanctions, and that sanctions are contributing to the suffering of people and undermine human flourishing and dignity.

The World Evangelical Alliance is not against sanctions as a tool in international relations. For example, in 2007, we endorsed the sanctions on Sudanese officials as well as on Burmese officials.

However, today, in many countries, the humanitarian and human rights impact of Unilateral Coercive Measures on civilians is disproportionate to their stated goals.

Thousands of Evangelical organizations and churches all over the world channel support, or used to channel support, to Evangelical churches and agencies in countries targeted by sanctions. These organizations and churches are relatively small. They build personal connections and relationships as the basis of their partnership. And sanctions have, again and again, prevented churches all over the world from helping their local counterparts, and from helping those in need in countries like Cuba, Syria, Iran, Venezuela, or, previously, in Sudan, and now in Afghanistan, and in other countries.

One Christian organization working in Syria told us that they received an exemption from sanctions, to send money for their workers, but they did not receive an exemption for the relief and aid, and for anything other than salaries. So now, we have a Christian organization receiving only salaries. The workers cannot help those around them.

However, the reality is that the exemptions processes are inaccessible to most of this constituency. Most Churches and Christian organizations cannot overcome the financial and knowledge hurdles needed to apply for exemptions from sanctions. Some of the bigger organizations have a dedicated staff or a law firm supporting, but this is not the case of most of our constituency.

If a man is hungry and comes to the church for food, should the church push him away if he is on some government’s sanctions list? This delicate question is haunting many Christian organizations in Lebanon and Syria today.

One Christian organization shared with us that they are doing a random sampling of a percentage of their beneficiaries every month to verify and document that those receiving essential food and non-food aid are not among the Syrians sanctioned by the United States and the European Union. Other Christian organizations have categorically refused to implement such surveys because they are not willing to deny humanitarian aid to anyone in need.

Afghanistan is the most recent example on the negative impact of UCMs. The country is on the brink of total economic collapse. The banking system is largely suspended, and aid agencies and the population cannot access sufficient cash to pay for basic supplies. At the same time, one Evangelical aid agencies shared with us that it’s been weeks that banks in the country of that agency have stopped transferring funding to Afghanistan. Yet again, a scenario is playing out that when the funding is most needed, the banks refuse to make the transfers. The people of Afghanistan are victimized twice.

Furthermore, there’s a trust problem with those who impose sanctions. In some countries, the local Christians are converts from another religion. And they are providing humanitarian aid, but are themselves in a very vulnerable situation. Some international Christian organizations that support organizations led by these converts do not apply for exemptions because they don’t want to reveal information about the recipient. It’s too dangerous. A Christian organization leader we spoke to said, “look what happened in Afghanistan. Some governments gave the Taliban the names of people at risk.”

So my question today is: Why do churches and well established and long-standing Evangelical organizations need exemptions to pursue their work? How can sanctioning countries justify embargoes?

Another dimension of the problem of sanctions, which makes futile even the exemptions, is bank over-compliance.

For example, Lebanese banks have refused to open bank accounts for Syrian refugees employed by Christian organizations—including one of which I was a board member—as a result of over-compliance.

Bank transfers to Lebanon for projects in Lebanon have been blocked by banks in Europe and the United States for the simple fact that a denomination’s name includes the word “Syria.” For historic reasons, the names of many church denominations include the phrase, “for Lebanon and Syria.” For example: the National Evangelical Synod of Syria and Lebanon; and The Supreme Council of the Evangelical Community in Syria and Lebanon.

Today, after a wave of heavy sanctions enforcement actions by the US Treasury, where global banks payed fines in the billions of US dollars, the global climate of financial institutions is one of increasingly over-compliance with sanctions. Essential life saving humanitarian aid, and support for churches in Syria, even with exemptions, either delayed or denied by the banking system.

One additional question, today, is: can over-compliance be considered unintended consequences? Or, are governments that impose sanctions responsible for the banks’ over-compliance, because they are putting the banks and everyone else in uncertainty?

When discussing sanctions, one of the often asked questions is whether a dire humanitarian situation is due to the sanctions or to corruption, incompetence and nepotism, and armed conflict.

If governments impose harsh and unpopular economic policies because they need foreign currency, are those governments to blame or the sanctions that denied them foreign currency? For example, the government in Syria imposes on every traveler to convert 100 US dollars to local currency upon entry to Syria. Cuba stopped accepting cash bank deposits in dollars, blaming tighter U.S. sanctions.

In our joint statement in March 2021 with the World Council of Churches and Caritas Internationalis, we said that in Syria, “all parties to the conflict bear responsibility for the suffering of the Syrian population” – not only the countries imposing sanctions.

Sanctions along with local factors causing and compounding the economic, social and humanitarian problems. And we advocate against all factors in our pursuit of justice and peace.

So, today, it is our observation that sanctions on many countries are failing the exact same people they claim to protect and compound the suffering of vulnerable populations. These “targeted” sanctions are, in effect, not discriminating between perpetrators of heinous crimes and the broader population.

In most countries, their impact – whether unintended or not, whether direct or indirect, whether over-compliance or not – is not proportionate to their stated objectives. It is not proportionate to their stated goal of bringing about a change in policy or activity by targeting countries, entities and individuals.”

Syria is the most flagrant example of the disproportionate impact (and I will not reiterate what Dr. Joel Veldkam already said on this panel with regards to Syria).

This proportionality test is made more problematic in light of years of research into the inefficacy of sanctions, and their repeated failure to fulfill their goals.

Now in addition to preventing humanitarian aid, and preventing church partnerships in general, sanctions undermine the churches’ peacemaking efforts.

We have seen in several countries Evangelical organizations pursuing peacemaking, but that their efforts have been hindered because of the uncertainty around the scope and implications of sanctions.

In Lebanon, an Evangelical organization pursuing peacemaking had a project to bring together parliament members from different communities and political groups. But could they include in their peacemaking a parliament member who is sanctioned by the United States? It is unacceptable that an Evangelical organization pursuing peacemaking and healing in society is hindered from doing so because of the uncertainty and vagueness of American sanctions.

In Cuba, an Evangelical leader shared with us that the embargo that the US has imposed on Cuba prevents political progress and transformation for Cuba, hinders partnerships to provide not only humanitarian aid, but also the broader commerce and exchange of ideas and the building of relationships with US churches and churches all over the world, that ultimately undermine both the work of the churches and the transition to democracy.

So what are we asking for?

We are asking for the removal of the sanctions that prevent churches from operating – whether for humanitarian work or for the churches to serve and assist people in need which is at the heart of our mission. We are asking for removal of sanctions that prevent the population of a given country from accessing basic needs and services, essential health supplies, including access to COVID-19 vaccines and treatments. And we are asking for the removal of sanctions, in war torn countries, when these sanctions inhibit the reconstruction of basic infrastructure destroyed by the ongoing conflict.

Until this happens, we ask sanctioning governments to take the following urgent action so that their sanction regimes are not impacting civilians, and not preventing our constituency from pursuing their vital work:

(1) Governments who impose sanctions need to exclude in law and in practice humanitarian work and the work of churches. Christian and humanitarian organizations should not have to deal with exemptions.

(2) Governments and donors should invest more resources, establish more accessible mechanisms, to assist churches and aid organizations, small and big, to overcome the various sanctions regimes and channel the aid and support needed. Churches and aid organizations should not bear the financial costs for navigating the complex sanctions regimes.

(3) All governments need to engage with their respective banking sector and need to address risk concerns so as to ensure fund transfers for humanitarian goods and for churches can continue unimpeded, and to ensure that donor funds to support aid can reach countries under sanction quickly.